pkb contents > design | just under 4539 words | updated 02/12/2018

Herbert Simon's definition (1969, p. 55) of design as the “transformation of existing conditions into preferred ones” is very popular. Also, from the editor's introduction to Johan Redström's Making design theory: "All goods and services are designed. The urge to design --- to consider a situation, imagine a better situation, and act to create that improved situation --- goes back to our prehuman ancestors. Making tools helped us to become what we are --- design helped to make us human."

Per Jaime Snyder at University of Washington, the purpose of a specific design intervention may be (1) to solve specific problems, OR (2) to help people reach their potential (more ambitious).

Orginally applied in product development, design was imported into education in the late 1960s.

Per Norman (2013, p. 5), emphasizes "form and material".

Per Norman (2013, p. 5), emphasizes "understandability and usability".

Per Norman (2013, p. 5), emphasizes "emotional impact".

Per Rams (n.d.; an industrial designer), good design:

Per Labarre (2018), it is:

Norman's fundamental principles of design (2013, p. 72):

Per Norman, a good design is human-centered design --- "an approach that puts human needs, capabilities, and behavior first" (Norman, 2013, p. 8). It entails "starting with a good understanding of people and of the needs that the design is intended to meet". "This understanding comes about primarily through observation, for people themselves are often unaware of their true needs, even unaware of the difficulties they are encountering"; it also comes in the form of principles from psychology and HCI. Finally, the approach involves iteration --- "rapid tests of ideas ... after each test modifying the approach and the problem definition".

Norman's (2013) conceptual model of the brain involves three levels of processing, with emotion and cognition (conscious and subconscious) tightly interrelated. This model is presented at-length in his book Emotional design. Designers should consider how their product, service, process, etc. impacts each level of processing:

"Visceral responses are fast and completely subconscious. They are sensitive only to the current state of things" (p. 51; see notes on trauma). Emotions at this level are reactions of calmness and anxiety (p. 55).

"The behavioural level is the home of learned skills, triggered by situations that match the appropriate patterns. Actions and analysis at this level are largely subconscious. Even though we are usually aware of our actions, we are often unaware of the details ... all we have to do is think of the goal and the behavioral level handles all" (p. 51). Emotions at this level are pattern-based or intentional expectations of hope and fear, as well as outcomes-related emotions of relief or despair (p. 55).

"The reflective level is the home of conscious cognition ... where deep understanding develops, where reasoning and conscious decision-making take place ... Reflection is cognitive, deep, and slow. It often occurs after the events have happened ... [e.g.] adding causal elements to experienced events" (p. 53; see notes on learning and notes on mindfulness). Emotions at this level are judgements of satisfaction, pride, blame, anger, guilt, etc. (p. 55).

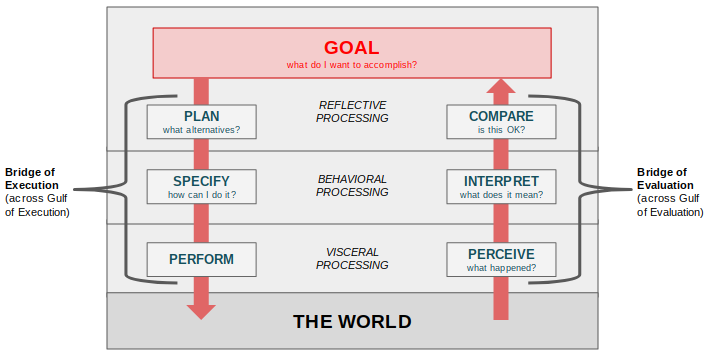

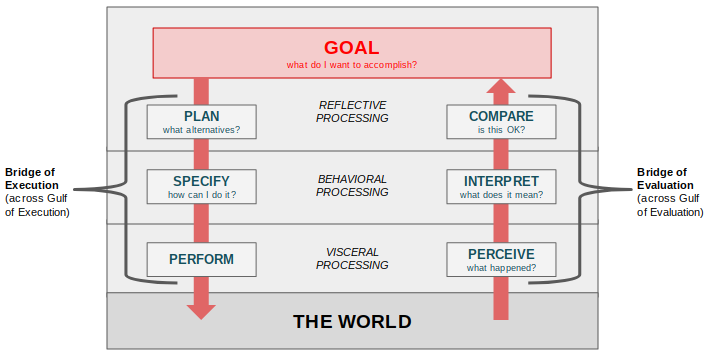

Norman's (2013) model of action (relevant to productivity) is also a model of interaction with a system (relevant to design).

Between a person (processor) and the world are two gulfs:

To cross the Gulf of Execution, a person must:

To cross the Gulf of Evaluation, a person must:

In this model, the agent may begin by forming a goal ("goal-driven behavior") or by reacting to the world ("data-" or "event-driven behavior"; pp. 42-43). Regardless, the agent is empowered to act by a robust, suggestive conceptual model, such as might come from systems thinking, and by depersonalizing the situation (as promoted by positive psychology) rather than blaming themselves (p. 37). This empowerment contrasts with a state of "learned" or "taught helpnessness" (p. 62).

From processing model:

| Level | Implication |

|---|---|

| VISCERAL | attend to "immediate perception ... [because] style matters: appearances, whether sound or sight, touch or smell" (p. 51) |

| BEHAVIOURAL | train/guide behavior by establishing expectations and providing feedback (p. 52) |

| REFLECTIVE | (this is the realm of interacting with tools in an artful or craftwork way; it has been neglected by designers pursuing user friendliness, according to Douglas Engelbart (in Levy, 2016, pp. 5-6) |

From interaction model,

At least two kinds:

Per Norman (2013, pp. 6 & 8):

These are "dark patterns", coined and classified by Harry Brignall (n.d.):

"The design thinking process is best thought of as a system of overlapping spaces rather than a sequence of orderly steps. There are three spaces to keep in mind: inspiration, ideation, and implementation. Think of

Per Jaime Snyder (2018) at University of Washington:

Per Birsel (2015):

Per Beyer & Holtzblatt (1999):

| Name | Action | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Contextual Inquiry | Talk to specific customers while they work | Reliable knowledge about what customers do and what they care about |

| Work Modeling | Interpret the data in a cross-functional team | Create a shared perspective on the data |

| Consolidation | Consolidate data across multiple customers | Create a single statement of work practice for your customer population |

| Work Redesign | Invent solutions grounded in user work practice | Imagine and develop better ways to work |

| User Environment Design | Structure the system to support this new work practice | Represent the system for planning, marketing, UI design, and specification |

| Mockup & Testing | Iteration with customer through paper mockups | Early verification of design before any ideas are committed to code |

| Implementation Design | Design the implementation object model or code structure | Define implementation architecture ensuring support of work structure |

| Design Scenario | Recommended Application of CD |

|---|---|

| FAST FEEDBACK: You're in field test. Your manager wants to know, "What are the 10 most important problems to fix before we ship?" Or you have a product in the field. You are asked, "What are the key usability problems in this part of the interface?" | Perform contextual inquiries with four to eight users at a minimum of four field test sites. Conduct interpretation sessions, capturing notes but no models. Create an affinity diagram to view the issues and write a report. |

| NEXT VERSION: You're working on the next version of your product. You know you want to support a certain task better, or extend it to support a new task. | Interview 8 to 12 users playing two or three roles in all at four to six sites. Take notes during your interpretation sessions, as well as sequence, artifact, and physical models. Consolidate the sequence models to see the structure of the task. If they are interesting, consolidate the artifact models to see strategies and intents. Create a low-level vision and storyboard, showing details of the users' interaction with the system. Design the UI and test it with paper prototypes. |

| NEW PRODUCT: You're designing a new product for a market. | Follow the whole process, including the affinity diagram and all models. Ifyou lack time, skip building a User Environment Design and go straight to UI design and paper prototypes. |

| NEW MARKET: You're defining a product strategy for a market you've never addressed. | Follow the whole process using a vision. Conduct 15 to 20 interviews, covering as many roles as you can---go for breadth, not depth, of understanding. End with a vision defining various product you might deliver. Analyze the vision to decide which products to pursue, and conduct another round of in-depth interviews to design them. |

Process, per Beyer & Holtzblatt (1997):

Principles, per Beyer & Holtzblatt (1997):

See notes on modeling for notation and examples; also see notes on documentation; performance management/process improvement; and information systems project management.

Per Beyer & Holtzblatt (1999, p. 35), "Five different models provide five perspectives on how work is done:

(For small projects, sequence and artifact models may be sufficient.)

"Together, the affinity diagram and consolidated work models produce a single picture of the customer population a design will address. They give the team a focus in the design conversation, showing how the work functions as a whole rather than breaking it up in lists. They show what matters in the work and guide the structuring of a coherent response, including system focus and features, business actions, and delivery mechanisms" (Beyer & Holtzblatt, 1999, p. 36):

"The redesigned work practice [NB: not the redesigned technology; the focus is still on the customer] is portrayed in a vision, a story of how customers will do their work in the new world we invent. A vision includes the system, its delivery, and support structures to make the new work practice successful. The team develops the details of the vision in storyboards, 'freeze-frame' sketches showing scenarios of how people will work with the new system ... when you make your use cases, use your storyboards as a guide ... " (Beyer & Holtzblatt, 1999, p. 39).

Diagrams in UED are meant to express the function of a system, abstracted away from its interface: "[show] every part of the system, how it supports the user's work, exactly what function is available in that part, and how the user gets to and from other parts of the system" (Beyer & Holtzblatt, 1999, p. 40).

Paper prototyping of an interface ---- "using Post-it notes to represent windows, dialog boxes, buttons, and menus" (Beyer & Holtzblatt, 1999, p. 40).

(this list per Friedman & Hendry, 2012)

See qualitative research methods:

Design thinking is for generating ideas. It draws on user research/contextual inquiry; it contributes to strategy and performance management as well as product and service design. Vassallo (2017b) urges the incorporation of systems thinking into design thinking, to cope with global complexity.

"Design thinking incorporates constituent or consumer insights in depth and rapid prototyping, all aimed at getting beyond the assumptions that block effective solutions. Design thinking — inherently optimistic, constructive, and experiential — addresses the needs of the people who will consume a product or service and the infrastructure that enables it. Businesses are embracing design thinking because it helps them be more innovative, better differentiate their brands, and bring their products and services to market faster. Nonprofits are beginning to use design thinking as well to develop better solutions to social problems. Design thinking crosses the traditional boundaries between public, for-profit, and nonprofit sectors. By working closely with the clients and consumers, design thinking allows high-impact solutions to bubble up from below rather than being imposed from the top" (Brown and Wyatt, 2010, p. 32).

Keller (1983) credits Gordon (1961) for developing the concepts of divergent and convergent thinking under the banner of "synectics".

"'Empathy' was Ideo founder David Kelley’s shorthand for in-the-weeds ethnographic research. And, to be fair, that’s what some design thinkers still have in mind. But as design thinking has grown in popularity, some of its core tenets have been watered down or misapplied. Perhaps as a result of overuse, when most designers talk about empathy, they don’t seem to me to be referring to fact-gathering at all, but something more like feeling-broadcasting. Empathy in design has gone from an outward-facing action to an inward-turned affect. I think it might be too late to protect the design-thinking denotation of the word from the layman’s definition. Regardless, I would urge us as a discipline to practice rigorous evidence-based compassion, rather than trying to feel people’s pain" (Vassallo, 2017a).

vs. surveys, focus groups, interviews, etc. from user research, where you don’t see users interacting with objects:

Friedman & Hendry (2012):

Envisioning Cards have been used to:

Beyer, H., & Holtzblatt, K. (1997). Principles of contextual inquiry. In Contextual design: Defining customer-centered systems. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

Beyer, H., & Holtzblatt, K. (1999). Contextual design. Interactions, 6 (1), 32-42.

Birsel, A. (2015). Design the life you love.

Brignall, H. (n.d.). Types of dark patterns. Retrieved from https://darkpatterns.org/types-of-dark-pattern

Brown, T. & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from https://5a5f89b8e10a225a44ac-ccbed124c38c4f7a3066210c073e7d55.ssl.cf1.rackcdn.com/files/pdfs/news/2010_SSIR_DesignThinking.pdf

Carroll, J. M. (1999). Five reasons for scenario-based design.In HICSS '99: Proceedings of the Thirty-Second Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 3, 3051.

Dumas, J. & Redish, J. (1999). A practical guide to usability testing. Bristol, UK: Intellect Ltd.

Friedman, B. & Hendry, D. G. (2012). The Envisioning Cards: A toolkit for catalyzing humanistic and technical imaginations. In E. H. Chi & K. Höök (Eds.), Proceedings of the 30th Annual SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’12) (pp. 1145-1148). New York, NY: ACM Press.

Labarre, S. (2018, January 3). 10 new principles of good design. Co.Design. Retrieved from https://www.fastcodesign.com/90154519/10-new-principles-of-good-design

Levy, D. (2016). Mindful tech: How to bring balance to our digital lives. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Nielsen, J. (1993). Usability testing. In Usability engineering (pp. 165-206). San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann.

Nielsen, J. (1994). Heuristic evaluation. In J. Nielsen & R. L. Mack (eds.), Usability inspection methods, (pp. 25 – 62). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Norman, D. (2013). The design of everyday things (revised and expanded edition). New York City, NY: Basic Books.

Rams, D. (n.d.). Good design. Vitsoe. Retrieved from https://www.vitsoe.com/us/about/good-design

Simon. H. (1969). Sciences of the artificial.

Vassallo, S. (2017a, April 26). The case against empathy. Co.Design. Retrieved from https://www.fastcodesign.com/90111831/the-case-against-empathy

Vassallo, S. (2017b, May 1). Design thinking needs to think bigger. Co.Design. Retrieved from https://www.fastcodesign.com/90112320/design-thinking-needs-to-think-bigger