pkb contents > project management | just under 4361 words | updated 10/27/2017

Project Life Cycle (PLC) per Watt (2014):

Systems Development Lifecycle (SDLC) per Annabi and McGann (2014), with my additions bracketed:

Others:

Also see why not use an IS?

IT/IS projects often suffer major delays and budget overruns. Best practices to avoid or limit these unwelcome outcomes, per Bloch, Blumberg, and Laartz (n.d.) as well as lecture content by Dr. Sean McGann and Barrett Rodgers:

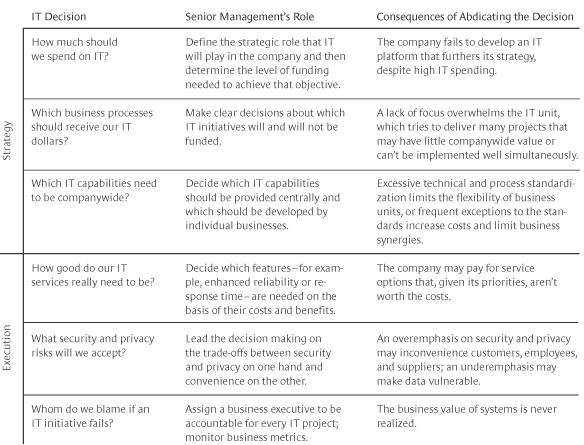

PESTEL, Porter's five, and SWOT/SLOT analyses are more common in the context of organizational strategic planning, but they can also be scoped to evaluate the desirability and feasibility of projects. Per Ross and Weill (2012), there are six strategic decisions that must be made at the outset of a project, but shouldn't be made by IT people:

Systematic review of the broadest trends and forces that constitute the business environment, to identify the implications for organizational strategy (since projects should be related to an organization's strategic goals):

Framework for evaluating the intensity of competition in a specific market or industry, which may have implications for whether a project is worth undertaking or may point to profitable niches:

Framework for making connections between a company's external landscape and internal characteristics (which can be restricted to the scope of a single project). Data is collected and sorted into a matrix, with one matrix for each alternative under consideration:

Also called need-gap analysis, need analysis, or need assessment. Gap analysis is a way of ensuring that planned actions align with objectives and present a reasonable pathway from the current reality to the desired state. (The 5 whys or fishbone/Ishikawa/cause-and-effect diagrams may be useful in analyzing the current reality to identify possible actions; see notes on process improvement.)

| Objective | Reality | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 12 widgets daily | 2 widgets | Hire more workers |

The general aim of stakeholder analysis is to identify stakeholders; analyze their interests and expectations; categorize interests and expectations based on importance and level of stakeholder influence; and develop an action plan that delimits roles for different stakeholders. Stakeholder analysis is important for managing the scope, influence and interorganizational politics of a project, as well as ensuring that projects address all relevant needs (including social equity goals).

Different authors present different stakeholder typologies. Per Leffingwell (2010):

Two typologies per Rabinowitz (n.d.):

| Low interest | High interest | |

|---|---|---|

| High influence | Latents | Promoters |

| Low influence | Apathetics | Defenders |

Once identified, decisions must be made about levels of stakeholder involvement. A RACI plan can capture stakeholder roles as well as roles for those involved in executing the project. Per Kantor (2012):

Facilitates organizational change by enumerating the forces that help or hinder an organization's ability to make change (note that individual people may constitute a force).

Example force field analysis

Overall, a business case must clearly outline a problem and a solution. If it's a proposal (meaning you must convince someone to hire you), you also need to demonstrate your credibility and capacity to deliver the solution.

Per Tom Sant as summarized by Obuchowski (2015):

| Problem with business proposal | Remedy |

|---|---|

| Failure to focus on the client’s business problems and payoffs; the content sounds generic. | Research the client |

| No clear differentiation of this customer compared with other customers. | |

| Failure to offer a compelling value proposition and clear solution. | |

| No persuasive structure --- the proposal is an "information dump". | Use structuring devices and simple language |

| Key points are difficult to read because they’re full of jargon, too long, or too technical. | |

| Key points are buried --- no punch, no highlighting. | |

| Credibility killers --- misspellings, grammar and punctuation errors, use of the wrong client’s name, inconsistent formatting, and similar mistakes. | Proofread |

Per Clayton (2003):

Per Hill & Cantera (2015):

Per Sheen (2015), scope creep is pervasive. Scope should be clearly addressed during the project initiation phase by (1) listing what's in and out of scope, provided stakeholders agree about scope; or (2) establishing scope ranges AKA scope tolerance parameters, which can be pinpointed as information emerges. A task is out of scope if it (1) doesn't make a direct contribution to the project goal, or (2) if time and money are binding constraints. Project the impact of requested additional tasks; never simply agree to perform them.

Phillips and Phillips (2010) discuss five different "levels" of project objectives in the case of instructional projects; I think this generalizes to many other kinds of projects.

In the traditional "serial" or lifecycle project management approach, requirements are translated into deliverables, deliverables are translated into a work breakdown structure (WBS), and the WBS is translated into a schedule and budget. Per Ambler (1999), about two-thirds of requirements elicited in this way lead to features that are never or rarely used, i.e. "spectacular levels of waste". In response, Agile tries to match development processes to the realities of constantly shifting requirements using:

Per Collella (2009), effective organizational communication requires a communications strategy, which includes (1) a core message that is not burdened with IT jargon, (2) the capacity to refine messages in response to stakeholder cues, and (3) assessment; a communications plan for institutionalizing and executing the strategy; and communication delivery skills.

Per PMI (2013):

Per Wikipedia (2017), a work breakdown structure (WBS) is a hierarchical decomposition of a project's total work. WBS elements are coded as 1.0, 1.1, 1.10.11, etc. Child elements must sum to 100% of their parent element, and so on until 100% of the project's total work is accounted for. Elements must be mutually exclusive, which is easier to accomplish if elements are outcomes, not tasks. There are different heuristics for establishing the terminal granularity of a WBS:

Once the hierarchy is established, terminal elements are budgeted and scheduled.

Designs must emerge from in-depth analysis of stakeholder (not just user) needs; requirements determination is the process of eliciting, analyzing, and synthesizing stakeholder needs so they can influence system design. Dennis et al. (2012) note that the analysis and design phases of a system implementation effort are very closely linked. That is, the product/s of requirements determination are "initial designs".

Per Dennis et al. (2012), requirements are expressed first as business requirements (from the perspective of stakeholders, including users), second as system requirements (from the perspective of developers). Requirements are also categorized as functional (what business tasks a system must perform) and nonfunctional (operational, performance, security, cultural and political requirements that affect how tasks are performed, and may arise from regulations such as Sarbanes-Oxley or the desire to comply with standards such as COBIT, ISO 9000, and the Capability Maturity Model).

Per StackExchange answers, is important to differentiate functional from nonfunctional requirements because:

Per Whitney (n.d.), Hooks (1994), and Gurd (2013), good requirements are:

Per Dennis et al. (2012), common problems with requirements are:

Per Dennis et al. (2012), requirements may be obtained from users, domain experts, existing processes, process improvement efforts, existing documents, and competing software using the following techniques (and see notes on qualitative methods):

A current state analysis produces models of the as-is system (see notes on system & process modeling techniques that are used). Per Dennis et al. (2012), a requirements determination process may begin with current state analysis; this, however, depends on:

The methodology used by the systems development team: "Users of traditional design methods such as waterfall and parallel development (see Chapter 1) typically spend significant time understanding the as-is system and identifying improvements before moving to capture requirements for the to-be system. However, newer RAD, agile, and object-oriented methodologies, such as phased development, prototyping, throwaway prototyping, extreme programming, and Scrum (see Chapter 1) focus almost exclusively on improvements and the to-be system requirements."

The amount of system change desired, i.e. BPA vs. BPI vs. BPR (see notes on process improvement for definitions and associated methods). The amount of change desired and amount of effort spent analyzing the as-is system are inversely related.

Per Whitney (n.d.), Dennis et al. (2012), and Ambler (1999), once gathered, requirements may be preserved, analyzed, and expressed in different ways:

Actors are the generic users of a system, e.g. customers, that might appear on a system diagram. Note that actors include other software as well as people. Leffingwell (2010) proposes some questions for identifying actors:

Per Wirfs-Brock and McKean (2001), primary actors are outside the system designers' control, and issue requests to the system; secondary actors respond to requests from the system.

Personas are different personalities that are meant to humanize a generic actor and show the range of users' needs. Personas are fictional but research-based biographies that reflect your understanding of your users; they are an exercise in fostering empathy and user-centered design. A primary persona is one whose needs are distinct enough to require a dedicated interface.

Per Ambler (n.d.), user stories describe, at a high level, the various actions users need to complete. User stories should be written by business or subject matter experts, using the form "As an X, I need to Y so I can Z." User stories are refined (split, grouped, reprioritized, etc.) throughout the development process. User stories may be grouped by their themes.

User stories can be decomposed into use cases, enumerating actors' interactions with the system as they pursue their goals. Leffingwell (2010) proposes some questions for identifying use cases:

Similarly, from Schneider and Winters (1998):

Per Wirfs-Brock and McKean (2001), use cases are written at different levels that, combined, depict the whole system:

There may be different paths through a use cases, perhaps corresponding to different personas; these paths are called use scenarios, and they may be depicted with a UML activity diagram or written as a series of bullet points (called a scenario form).

This is a two-column depiction of a use case/scenario, showing interactions between an actor and the system. User actions should be represented at the level of the user's intentions, i.e. their goals rather than the minute actions they may need to achieve their goals (although this depends greatly on the level of the system diagram).

Use cases may be depicted collectively with use case diagrams that:

Uses a table to indicate dependencies between requirements.

Individual use cases are expressed narratively in a flow-of-events AKA requirements definition report, usually including these elements:

Table format linking requirements with other information, e.g. requirement category, priority level, affected class, etc.

A special dictionary of acronyms, jargon etc. important for understanding system documentation. Per Wirfs-Brock and McKean (2001), a glossary entry should address the word's scope, typical values/example, related concepts, and significance; definitions should have the form "X is a [broader term] that [Y]" and avoid the phrases "is when", "is where" because they permit vagueness.

A informally-constructed network of concepts, reflecting entities and their interrelationships.

See notes on design thinking re: imagining the to-be system; see notes on system & process modeling and interfaces re: characterizing it.

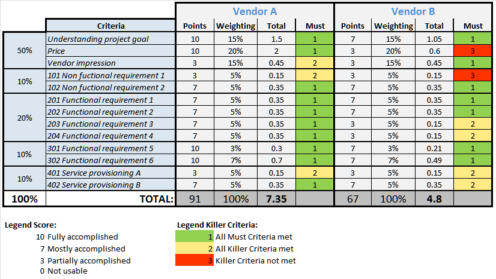

See notes on BI systems for information specific to selecting BI software. Per Lichtenberger (2012):

Per Clark (2016), in addition to "aesthetics and theatrics", a presentation should include:

Ambler, S. (1999). Comparing approaches to budgeting and estimating software development projects. Retrieved from http://www.ambysoft.com/essays/comparingEstimatingApproaches.html

Ambler, S. (n.d.). User stories: An Agile introduction. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.agilemodeling.com/artifacts/userStory.htm

Annabi, H. & McGann, S. (2014). Unit 1---What is MIS? In The real deal on MIS.

Clark, D. (2016, October 11). A checklist for more persuasive presentations. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2016/10/a-checklist-for-more-persuasive-presentations

Clayton, J. (2003). Writing an executive summary that means business. Harvard Management Communication Letter.

Collella, H. (2009). Effective communications: A strategy. Gartner.

Dennis, A., Haley Wixom, B., & Tegarden, D. (2012). Requirements determination. In Systems analysis and design: An object oriented approach with UML (4th ed., pp. 109–152). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Gurd, A. (2013, January 28). Managing your requirements 101 – A refresher. Part 4: What is traceability? Requirements Management Blog. Retrieved from https://www.ibm.com/developerworks/community/blogs/requirementsmanagement/entry/managing_your_requirements_101_a_refresher_part_4_what_is_traceability7

Hill, J. B., & Cantera, M. (2015). Use business outcomes to determine the scope of the “business process” to be improved (No. G00277312). Gartner.

Hooks, I. (1994). Writing good requirements. In INCOSE International Symposium (Vol. 4, pp. 1247–1253). Wiley Online Library. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/j.2334-5837.1994.tb01834.x/full

Kantor, B. (2012, May 22). How to design a successful RACI project plan. CIO. Retrieved from http://www.cio.com/article/2395825/project-management/how-to-design-a-successful-raci-project-plan.html

Leffingwell, D. (2010). Stakeholders, user personas, and user experiences. In Agile software requirements: Lean requirements practices for teams, programs, and the enterprise. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley Professional.

Lichtenberger, A. (2012, July 23). Six steps for a successful vendor selection. Retrieved from http://blog.itil.org/2012/07/allgemein/six-steps-for-a-successful-vendor-selection/

MITRE. (n.d.). Risk impact assessment and prioritization. In MITRE systems engineering guide. Retrieved from https://www.mitre.org/publications/systems-engineering-guide/acquisition-systems-engineering/risk-management/risk-management-tools

Obuchowski, J. (2005). A winning proposition: Crafting effective proposals. Harvard Management Communication Letter.

Phillips, J. J., & Phillips, P. P. (2010). The power of objectives: Moving beyond learning objectives. Performance Improvement, 49(6), 17-24.

Project Management Institute (PMI). (2013). Communication: The message is clear.

Rabinowitz, P. (n.d.). Identifying and analyzing stakeholders and their interests. In Community Tool Box. Work Group for Community Health and Development at Kansas State University. Retrieved from http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/participation/encouraging-involvement/identify-stakeholders/main

Rigby, D. K. (2015). Management tools 2015: An executive’s guide. Boston, MA: Bain & Company.

Ross, J. W., & Weill, P. (2002, November 1). Six IT decisions your IT people shouldn’t make. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2002/11/six-it-decisions-your-it-people-shouldnt-make

Schneider, G. & Winters, J. P. (1998). Applying use cases: A practical guide. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Sheen, R. (2015). How to manage scope creep [video]. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/video/2942763785001/how-to-manage-scope-creep

Watt, A. (2014). The project life cycle (phases). In Project Management. BCcampus Open Textbook Project. Retrieved from https://opentextbc.ca/projectmanagement/chapter/chapter-3-the-project-life-cycle-phases-project-management/

Whitney, E. (n.d.). Introduction to gathering requirements and creating use cases. Retrieved from http://www.codemag.com/Article/0102061

Wikipedia. (2017, March 28). Work breakdown structure. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Work_breakdown_structure&oldid=772556888

Wirfs-Brock, R., & McKean, A. (2001). The art of writing use cases. In Tutorial for OOPSLA Conference. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rebecca_Wirfs-Brock/publication/228393043_The_Art_of_Writing_Use_Cases/links/00b49517fe3053c449000000.pdf